April 30, 2024 felt like a fuse flame finally reaching the powder keg on the campus of Columbia University — which had attracted international attention because of protests condemning Israel’s response to the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack. Protesters linked arms at the entrance to Hamilton Hall. That morning, a group barricaded themselves inside, declaring their occupation of the building, which has been the setting for similar protests and occupations at least five times since 1968, according to The New York Times.

Columbia faculty members received a shelter-in-place directive from university administrators. By nightfall, a massive display of military might surrounded the campus — squadron after squadron of NYPD officers equipped with riot gear. The credentialed press had been banned, leaving the world to wonder who would bear witness to what was about to unfold.

But student journalists were on the scene, reporting from Pulitzer Hall, where Columbia’s J-school is housed and from the student radio station, WKCR-FM, where the on-air team coordinated coverage from field reporters. Student journalist Macyn Hanzlik-Barend stoically hosted the broadcast with a sense of calm and maturity that defied the escalating tension.

The field team reporters deployed to different areas of campus, filing live dispatches as police loudspeakers ordered them to disperse. “It’s a little bit chaotic,” one said. Another breathlessly reported, “Students are running away in fear.”

The officers directed the student press to leave the area, and though they complied, one of the journalists audibly asked, “Who is going to document this?”

Listeners learned, “They are pulling students from the entrance to Hamilton … throwing students. … They are completely flooding the building from all sides.” Fire alarms from inside Hamilton Hall began to sound.

Student journalists reporting from Pulitzer Hall were told to remain inside or risk arrest.

Protest signs line the encampment on the campus of Columbia University. These signs read, “Welcome to the People’s University for Palestine” and “Muslim American Society: From Mosques to Tents — Activism is worship.” Photo credit: thenews2.com

The live audio stream was so riveting and widely accessed that it periodically crashed, but the station team offered alternatives, directing listeners to the FM station and a livestream on Instagram instead. Over the course of two hours, they described the scene as protesters gathered behind police lines outside of campus, as students moved about, confused about where to go and what was going on, and as the NYPD entered Hamilton Hall through a second-floor window, shields up, guns drawn.

The on-air team read statements from the Administration but noted that students themselves had yet to receive any direct communication from the university about what was taking place on campus.

The coverage was exhaustive — a model of team reporting and grace under pressure — and exhausting for the student journalists who’d been on this “assignment” for weeks on end. Online, listeners applauded their professionalism and called for special Pulitzer Prize recognition for their work.

Hanzlik-Barend took time to acknowledge her colleagues, reciting their names individually.

When Hamilton Hall had been cleared — those inside arrested and removed from campus — there came a lull. It was an opportunity to dispel some rumors circulating online and in the national press. More than one of the student reporters audibly choked up when discussing how the police would be present on campus through the end of the semester.

At 10:37 p.m., Hanzlik-Barend said, “We might be able to play some music for the first time in many, many hours.”

Jazz filled the airwaves.

On May 2, the Pulitzer Prize Board put out a statement: “As we gather to consider the nation’s finest and most courageous journalism, the Pulitzer Prize Board would like to recognize the tireless efforts of student journalists across our nation’s college campuses, who are covering protests and unrest in the face of great personal and academic risk. We would also like to acknowledge the extraordinary real-time reporting of student journalists at Columbia University, where the Pulitzer Prizes are housed, as the New York Police Department was called onto campus on Tuesday night. In the spirit of press freedom, these students worked to document a major national news event under difficult and dangerous circumstances and at risk of arrest.”

Preparing for protests

Student presses nationwide are rising to the challenge of reporting on ongoing protests, but it hasn't been without peril. Two student journalists were arrested on Dartmouth’s campus while covering a protest this week. A pro-Israel group violently attacked the protest encampment at UCLA, and members of the group brutally assaulted four student reporters for the Daily Bruin.

To prepare student newsrooms for reporting in volatile situations, the Student Press Law Center published an April 2024 guide, “Know your rights when covering a protest.”

Brian Sherry was a freshman at the University of Pittsburgh when he joined the student-led daily, The Pitt News staff. He started out covering sports and became a sports editor. This summer, he’s serving as interim editor-in-chief; in the fall, he’ll be the managing editor. He’s a pre-law student and plans to specialize in media law.

Sherry said that the university has large Palestinian and Jewish communities, and since the war in Gaza began, they’ve been exchanging discourse and staging opposing demonstrations.

Protesters on the University of Pittsburgh’s campus chant, “Cease fire now.” Video credit: Brian Sherry

“This week, everything came to a head,” he said. A pro-Palestine “sit-in” became a more permanent encampment. Covering a campus with a big city as its home has helped the newsroom prepare for this moment in history. They frequently report on civil unrest and protests in Pittsburgh, including one that turned violent last year.

One of the challenges has been getting protesters and their organizers to speak on record, but they make every effort to talk with them, as well as with counter-protesters.

They seek comments from university administrators for every protest story.

Sherry said he monitors reader comments, which help the newsroom understand the array of opinions.

“This is definitely the biggest story I’ve had the opportunity to be part of. After I covered the protest on Sunday, my first day as editor-in-chief, I called my mom because I was a little excited. … I give a lot of credit to our former editor, Betul Tuncer. She really took us and this story under her wing. Even during her finals and on the day of her graduation, she was helping us out. We’re all proud of it, and I would say [our newsroom] understands the weight of the moment.”

Safety is paramount

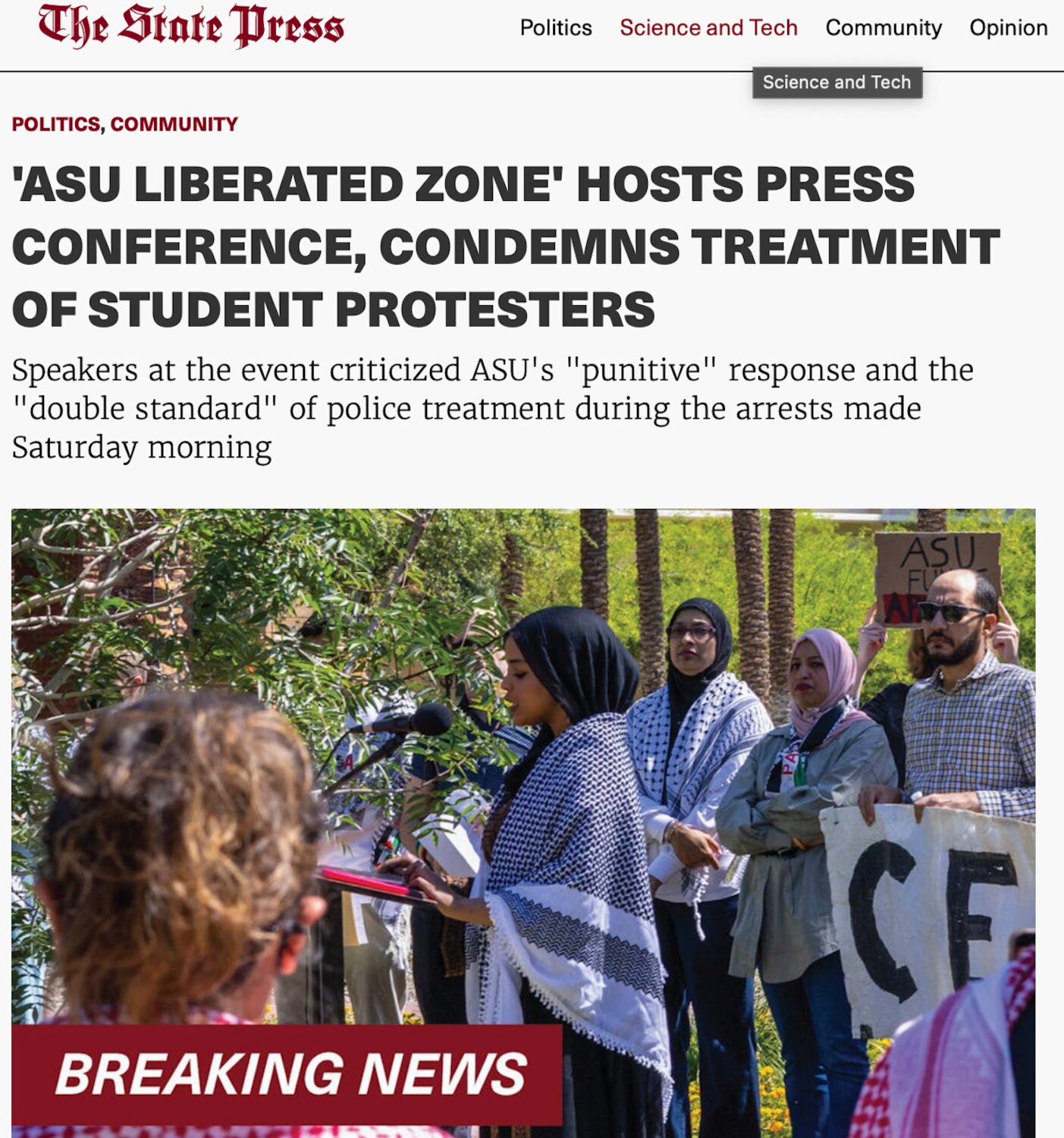

Angelina Steel just completed her final year at Arizona State University (ASU), where she majored in mass communications and minored in political science. During her undergraduate studies, she served in various roles at The State Press — photographer, photo editor, manager of the multimedia team, assignment editor and breaking news reporter — before becoming executive editor in her final year. She had the opportunity to intern at the Arizona Republic, Cronkite News and a social media startup.

Within days of Hamas’ October 7 attack, Jewish fraternities and sororities held a campus vigil for the people who’d been killed and taken hostage. Not long after, protests in support of the Palestinians were organized.

“The past couple of weeks have been the biggest protests we’ve seen on campus — definitely the most passionate,” Steel said. On April 27, 2024, there were 69 arrests on ASU’s campus.

Even as the semester neared the end and graduating students were focused on commencement, the newsroom at The State Press — ASU’s student newspaper — continued to report on campus protests.

The State Press newsroom is about 100 strong, with full-time and part-time student journalists and an editorial board. Early on, they had conversations about who would cover these events, the scope of which was beyond just one or two “beat reporters.” Politics and senior reporters and managing editors were deployed..

“We had to have as many hands on it as possible,” Steel said. They coordinated coverage on Slack and opened up lines of communication with the Administration.

One of the things they discovered immediately was that it was difficult to get protesters to speak with them. “Especially on the pro-Palestine side,” she explained. “A lot of those students have family back in Gaza — or used to have family back in Gaza. They’ve immigrated from the Middle East, so they genuinely feared for their safety, and they didn’t want their names to be out there. A lot of times, they wanted to be anonymous, or we’d offer to use only their first name.”

The national press has speculated extensively about protester motivations and whether large networks or organizations were stoking campus unrest. Steel said their team never found evidence of that.

“From both sides, there was never any underlying cruel or twisted motive. They just feel strongly about the conflict. The pro-Palestine side has been pushing for ASU to divest from companies that have operations in Israel, and they’re passionate about it. They don’t want to see their school funding war,” she reported. “On the other side, you have students who are very passionate about there being an Israel state and for the Jewish people to have a safe place in the Middle East. … There has been no real hate toward each other. I’m speaking for ASU, of course. It may be different at other schools in the country, but we’ve been fairly peaceful here.”

Student protesters have also demonstrated concern for their First Amendment rights, particularly after the school canceled an event at which U.S. Representative Rashida Tlaib planned to speak. Yet, the school welcomed right-leaning incendiary figures, like Joe Arpaio and Charlie Kirk, to give talks on campus.

The State Press newsroom has been keenly attentive to the safety of their reporters.

“We told all our reporters, ‘Your safety comes first. The minute things start to get violent or hostile — or [you] just don't feel safe being there — make that call and take a step back,’” she said. “‘We're not going to be mad if you do that. Your safety is our first priority over everything.’”

They’ve counseled reporters about having an escape plan, even a getaway car, and having a designated place for the team to safely meet. If they’re arrested or have their phones confiscated, they’re advised to write editor’s numbers on their arms in Sharpie.

“I’ve told them, ‘If something happens to you, don’t call your mom, don’t call your sister. Call me,’” Steel said. “‘That way, I can get in touch with our publisher and figure out where you are and how to get you out of there.’”

Earnest, dedicated and undaunted

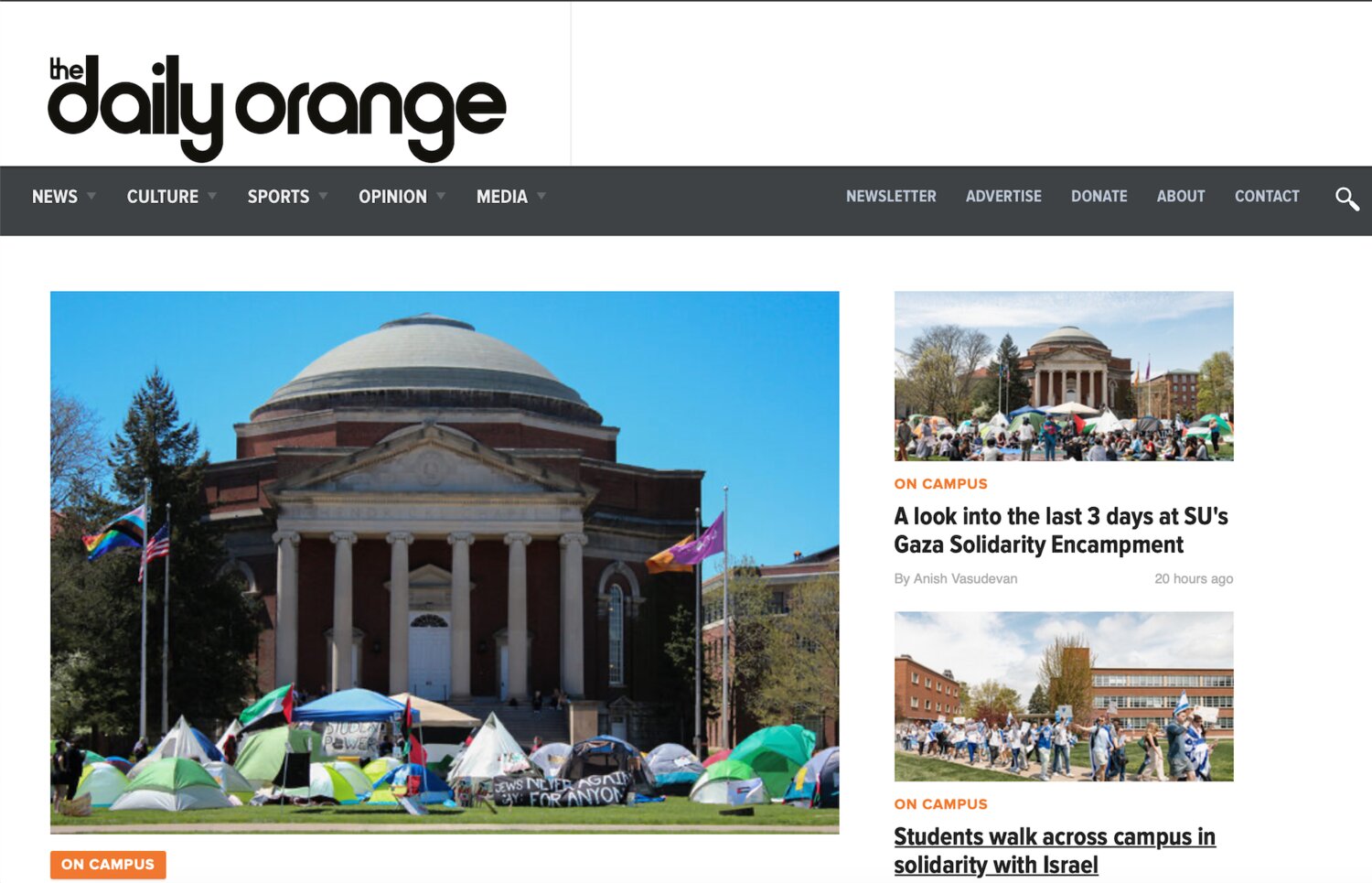

Anish Vasudevan started as a sportswriter for The Daily Orange at Syracuse University. In his junior year, he was named sports editor, and as a senior — majoring in magazine news and digital journalism at the Newhouse School — he became editor-in-chief. He was anticipating his May 11th graduation and a summer internship at ESPN — procured through the Asian American Journalists Association — when E&P spoke with him this week. Four days before, an encampment of protesters had formed on the university green.

The Daily Orange had been covering protests and counter-protests related to the war in Gaza since October 2023. It's a large newsroom with approximately 30 editors across categories, plus staff and contributing writers, visual journalists, designers and production staff. Since the protests began, the number of reporters tasked with the story varied, but this week, they’ve had seven or eight journalists, including Vasudevan, working four-hour shifts.

Vasudevan said “facts and stats” fuel their coverage. They launched a “live updates” thread on the website.

“We got a head start just looking at what other school papers have done, knowing this could happen here. This past Friday, we met with our team of editors and sat down to walk through everything that needed to happen. Kyle Chouinard, our managing editor, took the reins and made sure everyone knew who was covering what,” he said.

Created for The Daily Orange’s website, this graphic helped students understand the timeline of events that led to an encampment forming on the grounds of Syracuse University. Graphic by Cole Ross, digital design director, The Daily Orange

Created for The Daily Orange’s website, this graphic helped students understand the timeline of events that led to an encampment forming on the grounds of Syracuse University. Graphic by Cole Ross, digital design director, The Daily Orange

Members of the newsroom carry press credentials with them at all times, and they recently bought hoodies for reporters with The Daily Orange logo to identify their reporters.

Despite opposition protests, events on Syracuse’s campus have been notably peaceful. Thus far, there has been no law enforcement intervention, and the Administration has been tolerant of both the encampment and counter-protests.

Vasudevan has found the protesters to be unified in their intentions. They speak to members of the newsroom through designated spokespersons. “Basically, they want peace in the world, peace in Gaza. And they want the school — which has a lot of resources and investments in military technology that they feel are contributing to the war — to get away from that,” he said. Beyond interviews with those media designates, Vasudevan noted that many of the protesters are reluctant to speak with the press.

“I wouldn’t say they’re hostile, but more scared about us misconstruing their words, which I understand. I think our entire generation, Gen Z, is wary about the media and fake news,” he observed.

Before the encampment, they published an op-ed favorable to the pro-Palestine protesters; it angered Jewish students and Syracuse’s Jewish community.

“We had an instance where one of our reporters was wearing our hoodie in a Target, and someone straight up called her an anti-Semite, yelling it in her face. We also had people drive by our office and scream at us,” he recounted.

“We had to win back the trust of the Jewish students by publishing their letters to the editor. It’s about ensuring we’re always covering all sides,” he added.

Vasudevan remarked on the earnest dedication of the entire news team. He said there’s a misconception about Gen Z — that it’s a generation that doesn’t care about news. “But in our newsroom, we have 30 people come in every day, every week, who want to put their best foot forward and make sure these stories are properly told,” he said. “I want to reiterate that the only reason we’re able to do a good job covering these protests is because of the examples set by the Columbia Spectator, the Daily Trojan, the Daily Pennsylvanian — all of those newsrooms that had things happen a lot earlier than we did.”

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She's reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She's reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here